Book Review By My Dad K.S.Loganathan

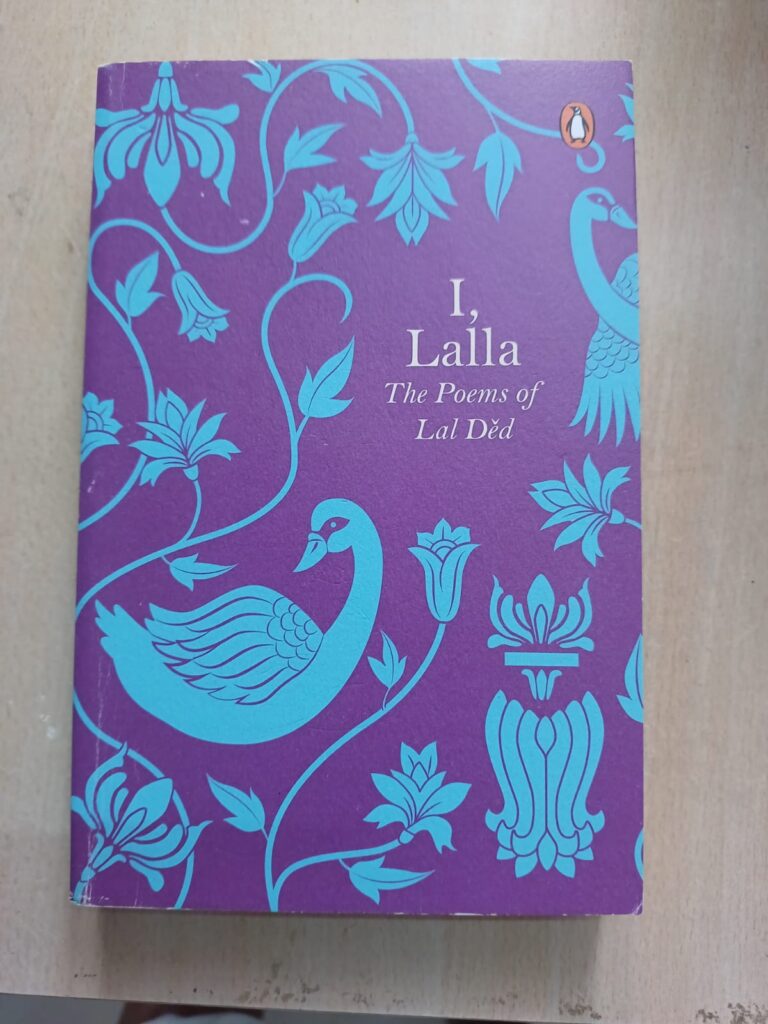

This is the remarkable life journey of a Kashmiri Brahmin woman mystic, Lal Ded ( 1320 – 1392 C.E.) a social rebel and religious seeker, who founded no philosophy school or religious movement, had no disciples, but in seeking spiritual enlightenment, she developed a true philosophy of life for all, irrespective of region or religion. Her birthplace Kashmir was a crucible of Indic, Greek, Chinese, and Persian cultural energies a millennium before her time during the Kushan Empire. Her four-line structured poems, called ‘vakhs’ (literally speech) are among the earliest compositions that have been part of the oral tradition of Kashmir which were preserved over generations in the collective memory as songs and hymns, some 700 years ago.

The Kashmiri language itself evolved during her lifetime as a mixture of Sanskrit, Punjabi, and Persian influences reflecting its multicultural heritage. Lal Ded’s poems are thus among the earliest known manifestations of Kashmiri literature. As they moved from oral to written and then to the printed script, which got translated into different languages, Lal Ded’s own Kashmiri identity has been viewed through different lenses, and her poems tinged with contemporary thinking. In this way, Lal Ded’s sayings have been polished over time.

Ranjit Hoskote, a Sahitya Academy Award Winner, has translated Lal Ded’s works in a labor of love, which took 20 years. In this book, he recaptures the jagged epiphanic power of her poetry, stripping away later Western recensions arising in translating ‘oriental’ religious literature into the English script. The 146 poems in this work are arranged progressively, beginning with self-doubt and moving to enlightenment and reverence in her spiritual journey. He says, ‘Lal Ded is not the person who composed these vakhs; rather, she is the person who emerges from these vakhs’.

Lal Ded, like Shankaracharya, Kabir, Guru Nanak, Namdev, and Akka Mahadevi, expressed devotion to God culminating in the realization of, or union with, the Supreme Absolute. At its core, Lal Ded’s spiritual odyssey is within the boundaries of Kashmiri Shaivism, Yoga, and Tantra. She conveys the essence of Kashmiri Shaivism in a simple way that is easily understood by the common people, for the benefit of humanity.

Kashmiri Shaivism, known as the trika system, is a three-fold amalgam of the transcendental, the material, as well as a combination of both; it inspires one toward both material and spiritual progress. Lal Ded’s vakhs form the foundation of much of the Kashmiri worldview that took shape later. Along with Sheikh Noor-ud-Din Wali (Nund Rishi ), the famous poet-saint who followed her, they formed the source of spiritual wisdom for both Hindu and Muslim communities in Kashmir, being the bulwark of Hindu and Sufi devotionalism that later flourished in northern India, particularly in the Delhi Sultanate and early Mughal eras.

Lal Ded discovers early that all creation has been produced by Vishnu’s play; / I came out, looking for the moon/came looking, light flying to light/All is Narayana! All is Narayana!/All is Narayana, You make my head spin/(16).

Lal Ded stresses the positive acceptance of the material world rather than the philosophy of escapism. Avoiding puritanical suppression and denial, we must exercise moderation in living and eschew the pursuit of wealth, power, and the pleasures of the senses. This practice will prepare us for the inward journey to realize God. She talks of the importance of the technique of breath control, kumbhaka which destroys residual bad karma and taints. The passage through life must be like the flight of the eagle, which leaves no trace.

Lal Ded emerges from her journey within to receive enlightenment and promote inter-faith harmony./Shiva lives in many places/He doesn’t know Hindu from Muslim/The Self that lives in you and others/ that’s Shiva. Get the measure of Shiva. (104)/

Lal Ded’s teachings rejected the ritualistic practices of the Brahmin priesthood, and being in the local dialect instead of Sanskrit, it became popular with the working classes. Lal Ded’s vakhs were likely interpreted by successive generations of writers who transcribed oral folklore onto their own moral codes and religious canons. The result is a syncretic ‘Kashmiriyat’ philosophy that synthesized Shaivism and Sufi Islam. In the recent Article 370 order of the Supreme Court, Justice Sanjay Kaul has lamented that Kashmiriyat, based on tolerance and inclusivity, sadly lies in tatters today. It is in recovering this shared culture that hopes lie for the future.

My views:

Lal Ded’s quest is to achieve a personal relationship with God, in the self-renewing space of an inclusive society. Her voice is of the masses who had no political influence and no stake in the cultural hegemony. Whether she was a crystalline diamond in the rough, cut and polished by anonymous contributors since her time, or an amorphous carbon life-form evolving with the times will never be known with certainty. It is hard to imagine a female mystic wandering about the Kashmir plains today to forge spiritualism and religious harmony.

Lal Ded’s poems take on a new life in Ranjit Hoskote’s adept translation. The poems are charged with ecstatic devotion. The book is a must-read for those who try to understand Kashmir’s troubled history, and his elaborate notes on the background of the poems help the reader understand the context. In the final vakh, Lal Ded invites the acolyte to don the robe of wisdom, commit her vakhs to memory, and strive to achieve redemption, overcoming the fear of death. Such people are the ‘ jivan-mukthas,’ ‘freed from life even while they live.’